Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

In the first of a major series looking at the evolving role of general practice within the cancer patient journey, specialist GPs Steven Beaven and Bridget Gwynne set the scene with an overview of cancer from a primary care perspective. Here, they examine changes in cancer incidence and survival, explain the concept of “overdiagnosis” and highlight the benefits of early diagnosis.

Dr Steven R Beaven Dr Bridget Gwynne Macmillan GP Advisers

Introduction

Life for general practitioners seems ever-changing. Contractual requirements are different every year and at the same time our patients are becoming more obese, tend to live longer and acquire more long-term conditions. We, as GPs, are able and expected to offer ever more care to our patients, and pressures mount with expectations about treating chronic diseases and patients with multi-morbidity.

Recognition of patients with a possible cancer diagnosis in primary care is challenging. Many patients present with symptoms that are vague or do not “fit” with referral guidelines.1 Access to diagnostics such as scanning and endoscopy has historically been variable, but is now improving. All GPs are aware of the impact of cancer diagnoses that are perceived by patients or their families as being “delayed”, but at the same time we are aware of our responsibility to use limited resources wisely, and there is a continuing debate about appropriate thresholds of risk that should trigger a referral.

Many people who have survived cancer, or are living with incurable disease, are now regarded as having a long-term condition. 2 These survivors may have late effects from their cancer or its treatment, and even those with metastatic disease may live for a long time with their cancer. Some people with metastatic colorectal or breast cancers, for example, may now survive for years with their disease, whereas twenty years ago survival would typically have been measured in months.

The changing face of cancer

Cancer statistics Statistics about cancer are available from many sources. National information is available from the Office for National Statistics (www.ons.gov.uk ), the Information Services Division (www.isdscotland.org), NHS Wales (www.wales.nhs.uk) and the Northern Ireland Executive (www.northernireland.gov.uk) for England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland respectively.

Information is also available from Cancer Research UK(www.cancerresearchuk.org/), and from several of the specific cancer charities. Statistics can be found for incidence, survival, trends over time and international comparisons.

Cancer incidence

The incidence of cancer has increased, with two key factors contributing to this change:

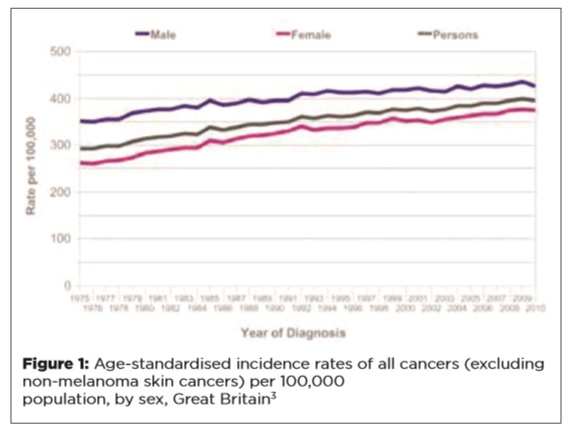

Firstly, the age-specific incidence of cancers has increased. These measures reflect the change in incidence that is independent of changes in the age structure of a population. In the period 1975-77 to 2008-10, the age-standardised incidence rate for all cancers in the UK rose by 22% in men and 42% in women, as shown in Figure 1.

Produced in collaboration with Macmillan Cancer Support

Secondly, our population is increasingly elderly, and as cancer incidence is strongly age-related this contributes to the increasing incidence of cancer. The incidence of cancer by age and new cases per year are shown in Figure 2.

The highest numbers of new cancers are currently seen in the eighth decade of life, but the age-specific incidence continues to rise into the ninth decade. Case numbers fall in the ninth decade as there are fewer octogenarians than septuagenarians, but as life expectancy increases, this may change.

The proportion of residents over 75 years in the UK is predicted to rise from 4.9 million (7.9% of the population) in the 2011 census, to 8.1 million (11.3% of the population) by 2030. 5

The increasing age-specific occurrence of cancer, combined with our increasingly aged population, will have a marked effect on the incidence of cancers and consequently on the resources of the NHS. Projections are available for cancer diagnoses to 2030. These are based on historical data, extrapolated and using assumptions about the effects of some screening, as well as changes, such as the reduction in use of hormone replacement therapy. 6

The common cancers

The common cancers remain prostate, lung and bowel for men, and breast, lung and bowel for women, accounting for 53% and 54% of all cancers, respectively. For men, bladder cancer, non-Hodgkins lymphoma and malignant melanoma are the next most common, while for women they are uterine and ovarian cancers and malignant melanoma.

The incidence of some cancers (e.g. breast, prostate and bowel) has increased, whereas some, such as stomach and cervical cancers, have become less common. Lung cancers have become less common in men but more common in women, reflecting historical changes in smoking patterns.

Over-diagnosis

“Over-diagnosis” of cancers – the identification of cancers which would not have caused ill-health during an individual’s lifetime – has become a concern. A hallmark of over-diagnosis of cancer is where an increase in incidence has occurred without a corresponding increase in attributable deaths, especially where there have been no changes in treatments that would explain improved survival.

For example, the increasing use of imaging (mainly ultrasound and CT scanning) has led to the recognition of small renal and thyroid cancers as incidental findings (so-called “incidentalomas”), which are likely to fall into this category.

Screening for breast cancer has identified cancers which may be “indolent” and unlikely to progress. The recent Independent Breast Screening Review, chaired by Professor Sir Michael Marmot, 8 estimated that 19% of screening-detected breast cancers may be over-diagnosed but acknowledged the paucity of evidence available and pointed out the net benefit of mammography in reducing mortality from breast cancer.

Autopsy studies have demonstrated how common occult prostate cancer is in elderly men, being present in 70% of those over 70 years old. It has long been recognised that a man is more likely to die with prostate cancer than from it. However, the availability of prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing has been associated with an increased identification of prostate cancer. The incidence of prostate cancer in the UK increased by 218% between 1975 and 2010. 9

Identification of a cancer will always be associated with anxiety for patients. Staging of a cancer and grading of its histology may not differentiate important from “unimportant” cancers. In the absence of robust, reliable techniques to characterise the likely behaviour of a cancer, there is pressure to treat, with the attendant risks associated with treatment, both in the short term and as late effects.

For example, 70% of men identified as having prostate cancer in societies where PSA testing is in widespread use are likely to have low risk disease, yet 90% of these men will get treatment, with attendant morbidity of erectile dysfunction, incontinence and bowel symptoms.

The decision to adopt a “watch and wait” policy for a patient with a small renal tumour identified as an incidental finding is clinically understandable, but we must recognise and understand its impact. A diagnosis of cancer is always a significant event for the patient and family, whatever its “clinical importance”.

General practitioners need to understand these concepts and to be able to discuss them with patients. Sharing uncertainties is challenging, but we have a responsibility to help our patients make informed choices.

Cancer survival

UK cancer survival rates have doubled in the last 40 years.

Figure 4 demonstrates changes in survival between 1971 and 2007 which are attributable to improvements in treatment, for example the improved prognosis for testicular cancers. There have been developments in treatment of breast, colorectal and prostate cancers that are reflected in improved survival, but over-diagnosis will also contribute to improved survival figures.

Improved survival and increasing incidence of cancer means that there is a rapidly increasing number of survivors of cancer. Macmillan Cancer Support estimates that the number of people living with cancer and beyond cancer will increase from two to four million in the next 15 years. 11

These patients will be a disparate group. Some may have no evidence of their cancer, they may remain well, and many may be regarded as cured. Others may have late effects of either their cancer or its treatment, be at risk of second primary cancers or may have recurrence of their cancer.

Patients who have had a cancer commonly describe their illness as a life-changing event. The increasing number of survivors of cancer will turn to their primary care team for care, information and support.

Early diagnosis – does it matter?

For some cancers, there is clear evidence that earlier diagnosis is associated with improved survival. A good example is colorectal cancer, in which earlier stage cancers have markedly better survival figures than later stage cancers (Table 1).

Lung cancers, with a much poorer general outlook, also show survival advantages associated with early stage diagnosis. Earlier diagnosis is associated with higher lung resection rates, which are in turn associated with improved survival. 14 Unfortunately, resection rates (and hence survival) are poorer in the UK than in some other European countries, and there are considerable geographical variations within the UK itself. Resection rates vary from around 6% in primary care trusts in the lowest quintile, to over 12% in the highest quintile. 15 This does not appear to be purely a function of deprivation, 16 but reflects variations in local services.

Statistics for many other cancers – breast, renal, bladder, ovarian, melanoma – show survival benefits from early stage diagnosis.

The International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership, a partnership of clinicians, academics and policymakers, is undertaking research aimed at improving understanding of the variations in cancer outcomes between different countries and within countries. Important factors might prove to include the following:

- Differences in patient behaviour after developing symptoms

- Patient access to both primary and secondary care

- Availability and capacity of diagnostics

- Type of healthcare system.

In some health services, patients have direct access to secondary care, thus bypassing the gatekeeper function of primary care.

Conclusion

We face an increasing incidence of cancer, and as a consequence of increasing incidence and improving survival, many more patients are living with cancer and requiring our care.

Our survival rates, while improving, lag behind those of many comparable western countries.

We know that earlier staging at diagnosis is associated with improved survival. The challenge of earlier diagnosis in general practice will be addressed in the next article.

References

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence – Referral for suspected cancer www.nice.org.uk/cg27

2. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Documents/GetInvolved/Campaigns/Campaigns/campaignsupdate/Darzi_longterm_29feb08.pdf

3. Cancer Research UK – http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/incidence/all-cancers-combined/ November 2013. Data provided by national cancer registries in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

4. Cancer Research UK – http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/incidence/age/November 2013. Data provided by national cancer registries in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

5. The Office of National Statistics

6. P Sasieni et al. Br J Cancer 2011;105:1795-1803 www.nature.com/bjc/v105/n11/full/bjc2011430a.html

7. Cancer Research UK – http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/incidence/commoncancers/ November 2013. Data provided by national cancer registries in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

8. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/breast-screening-review-exec_0.pdf

9. Cancer Research UK – http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/prostate/incidence/ November 2013. Data provided by national cancer registries in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

10. Cancer Research UK – http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/survival/commoncancers/ November 2013. Data provided by national cancer registries in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

11. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Aboutus/Ouresearchandevaluation/Researchandevaluation/Keystatistics.aspx

12. Cancer Research UK – http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/bowel/survival/ November 2013

13. Cancer Research UK – http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/lung/survival/#stage November 2013

14. www.ncin.org.uk/publications/data_briefings/variation_in_surgical_resection_for_lung_cancer_in_relation_to_survival

15. www.ncin.org.uk/publications/data_briefings/variation_in_surgical_resection_for_lung_cancer_in_relation_to_survival

16. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/6871/1871208.pdf

To read the second part in the series, click here