Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

The incidence of recurrent wheeze in young children is a common and growing problem in the UK. Rational management is highly dependent on sound identification of causes and proper diagnosis, both of which represent significant challenges for GPs. Child respiratory specialist Jayesh Bhatt explores the issues and the evidence base.

CASE HISTORY

Leyla, a 15 month old girl, has a history of frequent wheezy episodes from nine months of age.

Following the first episode in October, she was admitted for two days and was treated with prednisolone and inhaled salbutamol. She had rhinovirus on her respiratory secretions. Subsequently, she had wheezy episodes almost every month; the most recent hospital admission was for 10 days and included paediatric intensive care.

On all these occasions Leyla was given treatment with prednisolone, oxygen and nebulised bronchodilators. She remained symptom free in between episodes, but whenever she had a cold she seemed to get very severe wheezing illness.

Leyla’s parents are non-smokers but have a wood-burning stove in the house. Her mother suffers from asthma, but there is no other significant past medical history. Leyla was born at full term with no neonatal respiratory or bowel problems.

On previous examination her weight and height were tracking the 50th and 25th centiles respectively. There was no chest deformity; the chest was completely clear and no warning features were found on systemic examination.

At a subsequent consultation, more recently without colds, she is reported to become easily short of breath and to have a wheeze when crawling. You are able to confirm this in the clinic. There is also an associated dry cough, more noticeable at night time. She has frequent sneezing but no runny nose without colds and has moderate eczema. There is no food allergy and no history of discharging ear infections.

Discussion

Wheezing is a common symptom in pre-school children, with almost half of children having at least one episode of wheeze by the age of 6 years. 1 In the UK, the prevalence of wheezing illness in pre-school children seems to be increasing, 2 while the annual costs of caring for this patient group in the UK has been estimated to be around £53 million. 3

Definition and classification of wheeze

Wheeze has been defined as a continuous high-pitched sound, with “musical” quality, emitting from the chest during expiration.4 In 2008, a Task Force from the European Respiratory Society (ERS) proposed a pragmatic clinical classification which divides wheezing illness in pre-school children into episodic (viral) wheeze and multiple-trigger wheeze (MTW). 4

Episodic wheeze

Children with episodic (viral) wheeze are well between episodes. The most common viral triggers include rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), coronavirus, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus and adenovirus 5 – although in routine clinical practice microbiological diagnostic studies are rarely performed.

In young infants, episodic (viral) wheeze may be difficult to distinguish from acute bronchiolitis – not least because the definition used for this clinical syndrome varies in different parts of the world. In the UK, Australia and parts of Europe, bronchiolitis is defined as the presence of upper respiratory tract symptoms with coryza and cough preceding the abrupt onset of lower respiratory symptoms, with a variable degree of respiratory distress, feeding difficulties and hypoxia. On auscultation there are widespread crepitations. Wheeze may or may not be present.

In most of North America and parts of Europe, the term bronchiolitis is generally applied to all conditions involving expiratory wheeze with evidence of a respiratory viral infection such as rhinorrhoea and cough. 6

Whether or not the initial episode is classified as bronchiolitis is irrelevant, but recurrent wheezing is common following an initial infection with various respiratory viruses. 7,8

Various different hypotheses have been proposed to explain recurrent wheezing, including:

- Viral infections promote wheezing, mainly in predisposed children when exposed at a critical age . 9

- Intermittent virus-induced wheezing becomes persistent wheezing in the high risk, susceptible child. 10

Episodic (viral) wheeze most commonly declines over time, disappearing by the age of 6 years, but can continue into school age, change into multiple- trigger wheeze, or disappear at an older age. Other factors that influence the frequency and severity of episodes include the severity of the first episode, atopy, prematurity and exposure to tobacco smoke. 4

Multi-trigger wheeze

Viral infection is also one of the most important precipitants of MTW, but factors such as passive smoking exposure, allergens and exercise are also significant contributors. 4 It has been shown in a prospective birth cohort study that allergic sensitisation precedes rhinovirus wheezing but that the converse is not true. 11 Children with MTW may therefore have symptoms which are not confined to discrete episodes (interval symptoms), such as nocturnal cough and exercise-induced dyspnoea. The phenotypes defined in the Task Force report 4 are not exhaustive, and individual patients may not fit into the categories described. Moreover, there can be an overlap between phenotypes, and patients can move from one phenotype to the other. 12

When is a wheeze not a wheeze?

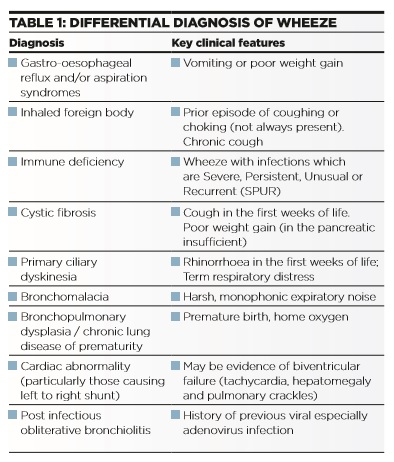

Diagnosis of wheeze may be complicated by the presence of other conditions that give rise to noisy breathing and which could be misidentified as wheeze, as well as the wide differential diagnosis of wheeze in young children (Table 1). Rational management is focused on exploring the true nature of noisy breathing, as summarised in Table 2.

- Parents may ascribe a different meaning to the word “wheeze” to that understood by health professionals. Most parents tend to be better at locating sounds than labelling them. 13,14

- Ruttle/rattle is another type of respiratory noise, which is lower in pitch, has a rattling quality and lacks any musical features. Parents may be able to feel this noise as a vibration over the baby’s back. 15 Ruttle may be related to excessive secretions or to abnormal tone in the larger airways. Wheeze and ruttle have quite distinct acoustic patterns when assessed objectively using acoustic analysis. 16 There is also a different response to ipratropium when assessed by computerised breath sounds analysis: a clear reduction in breath sounds intensity is evident at 5 minutes in infants with ruttle, but not until 20 minutes in those with wheeze, suggesting a different pathophysiology. 17

- Even among health professionals there are inter- observer variations in assessing wheeze using a stethoscope. 18 Furthermore, in pre-school children, lung function 19 and bronchoscopic findings 20 are different in those with parent-reported wheeze, as compared to doctor-confirmed wheeze.

- Risk factors and outcomes for different respiratory sounds also differ when children are followed up to school age. 21

In view of these difficulties, clinicians should undertake a detailed clinical assessment of each child that does not place undue weight on any one symptom, 22 and parent- reported asthma symptoms should be confirmed by paediatricians whenever possible. 23

Predictive markers

Longitudinal studies suggests that approximately 50% of wheezing children outgrow their symptoms. This is largely accounted for by transient early wheeze, which probably has no association with asthma. MTW, in contrast, is more likely to represent asthma. A recent review 24 summarises various predictive indices of subsequent asthma risk to help the clinician identify those children who will continue wheezing into older childhood. These indices appear to have high negative predictive values and can thus help identify the children who are at low risk of later asthma and those in whom prolonged therapy might not be useful. However, these indices remain imperfect at identifying children at risk of asthma. There is as yet no definitive biomarker to identify children with high-risk phenotypes who will go on to have persistent asthma.

Investigations of wheeze

While most children do not require further investigation, the decision should be guided by the history and examination findings 25 and may include:

- Documenting a normal chest x-ray. Chest x-ray should be requested if there is very severe wheezing, focal or assymetrical chest signs, associated prolonged (longer than 4 weeks) wet cough, or if any other red flag indicators (Table 3) are present.

- Cough swab if there is a wet cough

- Nasopharyngeal aspirate or throat swab for virology, if there is evidence of current respiratory infection

- Skin prick test or specific IgE to inhaled allergens can help establish atopic tendency and may identify a specific trigger

Children should always be referred for further investigations if there are red flag features in the history, if examination is suggestive of other pathology, or if the diagnosis is unclear or in doubt.

Key aspects in management

- Primary prevention is not possible, but avoidance of environmental tobacco smoke exposure should be strongly encouraged.

- Allergen avoidance is of limited value. A reduction of exposure to single allergens, such as house dust mite, does not reduce the prevalence of physician diagnosed “asthma” in the pre-school children.26 Environmental allergen reduction (e.g. occlusive bedding and mattresses) is expensive and dietary exclusion is inconvenient and intrusive. A multifaceted environmental exposure-reducing intervention may have to be adapted to the personal circumstances of patients at baseline.27

- Bronchodilators can improve parent- rated symptom scores 28 and measures of lung function. 29 While the routine use of bronchodilators cannot be recommended, a trial is justified and treatment continued if objective benefit can be demonstrated. 30 In children, the use of a spacer (rather than a nebuliser) to administer a beta 2 agonist does not significantly reduce the risk of admission but does reduce the length of stay in the emergency department. Use of a spacer has been associated with significantly fewer adverse effects, such as tachycardia. 31 Adding an anticholinergic bronchodilator improves symptom scores after 24 hours 32 and reduces admissions. 33

- Oral corticosteroids: The practice of giving parents a supply of oral prednisolone to administer to their children at the first sign of a wheezing episode cannot be justified as there is no benefit in terms of symptom scores, number of outpatient visits, number of attacks or hospitalisations.34,35 For children presenting to the emergency department, the evidence for using oral steroids is conflicting36,37 and remains in equipoise. Pragmatically, oral steroids should be reserved for a child with an atopic background and frequent and severe wheezing requiring oxygen on admission. For these children, it would be reasonable to give a short course of oral prednisolone as one would for an older child with asthma.

- Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS): High dose ICS used intermittently are effective in children with frequent episodes of moderately severe episodic (viral) wheeze or multiple-trigger wheeze, but this is associated with short term effects on growth and cannot be recommended as routine treatment. 38 Maintenance treatment with low to moderate continuous ICS is ineffective for pure episodic (viral) wheeze; it does, however, work in multi-trigger wheeze but does not modify the natural history of the condition. Where inhaled steroids are used, they should be stopped if symptoms do not improve, and treatment breaks should be employed to see if the symptoms have resolved or continuous therapy is still required. This issue is well summarised in a recent review. 39

- Montelukast: Maintenance as well as intermittent montelukast has a role in both episodic and MTW. 40-43

- Nebulised hypertonic saline: Hypertonic saline inhalation, an airway surface liquid hydrator therapy, significantly decreases both the length of stay and the absolute risk of hospitalisation in pre-school children presenting with acute wheezing episode to the emergency department. 44

- Education: Good multidisciplinary support and education is essential in managing this common condition. 39

CASE HISTORY CONTINUATION

Leyla’s management

Leyla is seen in the respiratory clinic, a careful history is obtained and base line investigations performed. Treatment is sequentially commenced with inhaled fluticasone via spacer and then montelukast – with good response. Her symptoms improve and there is a dramatic decline in the need for attendance at the emergency department and subsequent hospital admissions. She is given a break from treatment over the summer and is actually able to stay off inhaled fluticasone for the entire summer period. Currently she remains only on oral montelukast and has not had any admissions for nine months.

Dr Jayesh Bhatt Consultant Respiratory Paediatrician, Nottingham Children’s Hospital

References

1 Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, N Engl J Med 1995;332:133-8.

2 Kuehni CE, Davis A, Brooke AM, et al . Lancet 2001;357:1821-5.

3 Stevens CA, Turner D, Kuehni CE, et al . Eur Respir J 2003;21:1000-6.

4 Brand PLP, Baraldi E, Bisgaard H, et al . Eur Respir J 2008;32:1096-110.

5 Papadopoulos NG,.Kalobatsou A. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;7:91-5.

6 Everard ML. In Taussig LM, Landau LI, eds. Pediatric Respiratory Medicine, Mosby, 2008.

7 Bont L, Aalderen WM, Kimpen JL. Paediatr Respir Rev 2000;1:221-7.

8 Lemanske RF, Jr., Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, et al . J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;116:571-7.

9 Boehmer AL. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2010 ;11(3):185-90.

10 Jackson DJ. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol . 2010 ;10(2):133-8.

11 Jackson DJ, Evans MD, Gangnon RE, et al . Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2012 ;185(3):281-5.

12 Schultz A, Devadason SG, Savenije OE, et al . Acta Paediatr 2010;99:56-60.

13 Cane RS, Ranganathan SC, McKenzie SA. Arch Dis Child 2000;82:327-32.

14 Cane RS,.McKenzie SA. Arch Dis Child 2001;84:31-4.

15 Elphick HE, Sherlock P, Foxall G, et al . Arch Dis Child 2001;84:35-9.

16 Elphick HE, Ritson S, Rodgers H, et al . Eur Respir J 2000;16:593-7.

17 Elphick HE, Ritson S, Everard ML. Arch Dis Child 2002;86:280-1

18 Elphick HE, Lancaster GA, Solis A, et al . Arch Dis Child 2004;89:1059-63.

19 Lowe L, Murray CS, Martin L, et al . Arch Dis Child 2004;89:540-3.

20 Saglani S, McKenzie SA, Bush A. Arch Dis Child 2005;90:961-4.

21 Turner SW, Craig LC, Harbour PJ, et al . Arch Dis Child 2008;93:701-4.

22 Mellis C. Pediatr Clinic North Am 2009;56:1-17.

23 Mohangoo AD, de Koning HJ, Hafkamp-de Groen E, et al . Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45(5):500-7.

24 Bacharier LB, Guilbert TW. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 ;130(2):287-96

25 Saglani S, Nicholson AG, Scallan M, et al . Eur Respir J 2006;27:29-35.

26 Mass T, Kaper J, Sheikh A, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;Issue 3. Art. No.: CD006480.

27 Maas T, Dompeling E, Muris JW, et al . Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011 Dec;22(8):794-802

28 Conner WT, Dolovich MB, Frame RA, Pediatr Pulmonol 1989;6:263-7.

29 Kraemer R, Frey U, Sommer CW, Russi E. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;144:347-51.

30 Carroll WD, Srinivas J. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2013 ;98(3):113-8.

31 Cates CJ, Crilly JA, Rowe BH. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;Issue 2. Art. No.: CD000052. DOI:10.1002/14651858. CD000052.pub2.

32 Everard M, Bara A, Kurian M, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001279. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001279.pub2.

33 Plotnick L,.Ducharme F. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;Issue 3. Art. No.: CD000060. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD000060.

34 Grant CC, Duggan AK, DeAngelis C. J Pediatr 1995;96:224-9. 35 Oommen A, Lambert PC, Grigg J. Lancet 2003;362:1433-8.

36 Csonka P, Kaila M, Laippala P, et al . J Pediatr 2003;143:725-30.

37 Panickar J, Lakhanpaul M, Lambert PC, et al . N Engl J Med 2009;360:329-38.

38 Ducharme FM, Lemire C, Noya FJ, et al . N Engl J Med 2009;360:339-53.

39 Bhatt JM, Smyth AR. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2011;12(1):70-7.

40 Bisgaard H, Zielen S, Garcia-Garcia ML, et al Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:315-22.

41 Knorr B, Franchi LM, Bisgaard H, et al . Pediatr 2001;108:E48.

42 Robertson CF, Price D, Henry R, Mellis C, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:323-9.

43 Bacharier LB, Phillips BR, Zeiger RS, et al . J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:1127-35.

44 Ater D, Shai H, Bar BE, et al . Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):e1397- 403.